France (III)

Metro rides, productivity, an infanticidal Christmas story (fun?), parking lots, and terrorism again.

Cardinal Lemoine

Growing up the child of a law student and a stay-at-home mom, I was anxious about money. I knew the kind of stress it put on parents with six-figures’ worth of student debt. I remember my mom pulling the couch from the wall, searching for fallen change so we could afford a pizza. I remember working a paper route through primary school to pay for hockey. Eventually, our circumstances changed, but the money anxiety never left.

I was also a bit of a chunkster. At the sight of a vending machine, I'd press up against the glass and gawk frothily. But in that five or six year stretch, another dollar spent was another reason to start an argument. By no means did I grow up in want of anything, but little luxuries like vending machine snacks were things for which I did not feel comfortable asking. So I rarely did.

Twenty years later, I'm waiting for the metro to Grenelle station in one of the most expensive cities on earth. There's no one around. It's curfew soon, so the cross-town is a ghost town. It's just me and a vending machine down the platform. A lit cabinet full of glossy European chocolates and candies as new and tempting as the Canadian ones when I was a kid.

I punch in the coordinates of a drink. Two euro. Quick math. That's three ten.

Fuck it, gimme.

I retrieve the bottle, twist the cap, lower my mask, take a sip. Feel the sugar.

Feels good. Worth it.

Feels like the most productive thing I've done in my two months in France.

I look around the empty station and think: Eight year old me would be proud. He'd condone this. He'd be all about this, actually. He'd sign off on every decision responsible for bringing me right here, right now.

A metro sign hangs from the curved ceiling tiles. CARDINAL LEMOINE. Underneath are a bunch of words written in a language I still can't figure out. Then, somehow, it registers. Where I am. How far I've gone. How unlikely it is to be here. How impossible this all should be. How this is a part of something right. That even if I haven't figured it out, it's still right. How the pursuit to be a better, more discerning person has taken me to Paris, of all places. Paris! Eight year old me would be happy to see me. This registers like brick against glass. This belief in my own kind of excellence.

I've been abroad for months now, stringing together Big Moment gratifications. But the best yet was a small one: Standing alone on the platform, drinking some forgettable sugary bullshit, waiting for the train. When it arrives, I turn the latch on the door, an old little manual thinga madoo. It springs open. I step into the crowded car and forget, for a second, where I'm going.

/

French Productivity

It's a myth that French people are lazy. But it's true that they work a lot less. The French have 11 public holidays, 35 hour work weeks, and, on average, 30 whole days of statutory paid vacation per year. They're only able to enjoy these privileges because, as a society, they're highly productive, even by European standards. They clock fewer hours, yes, but their total labour productivity smokes ours re: return on work hours invested.

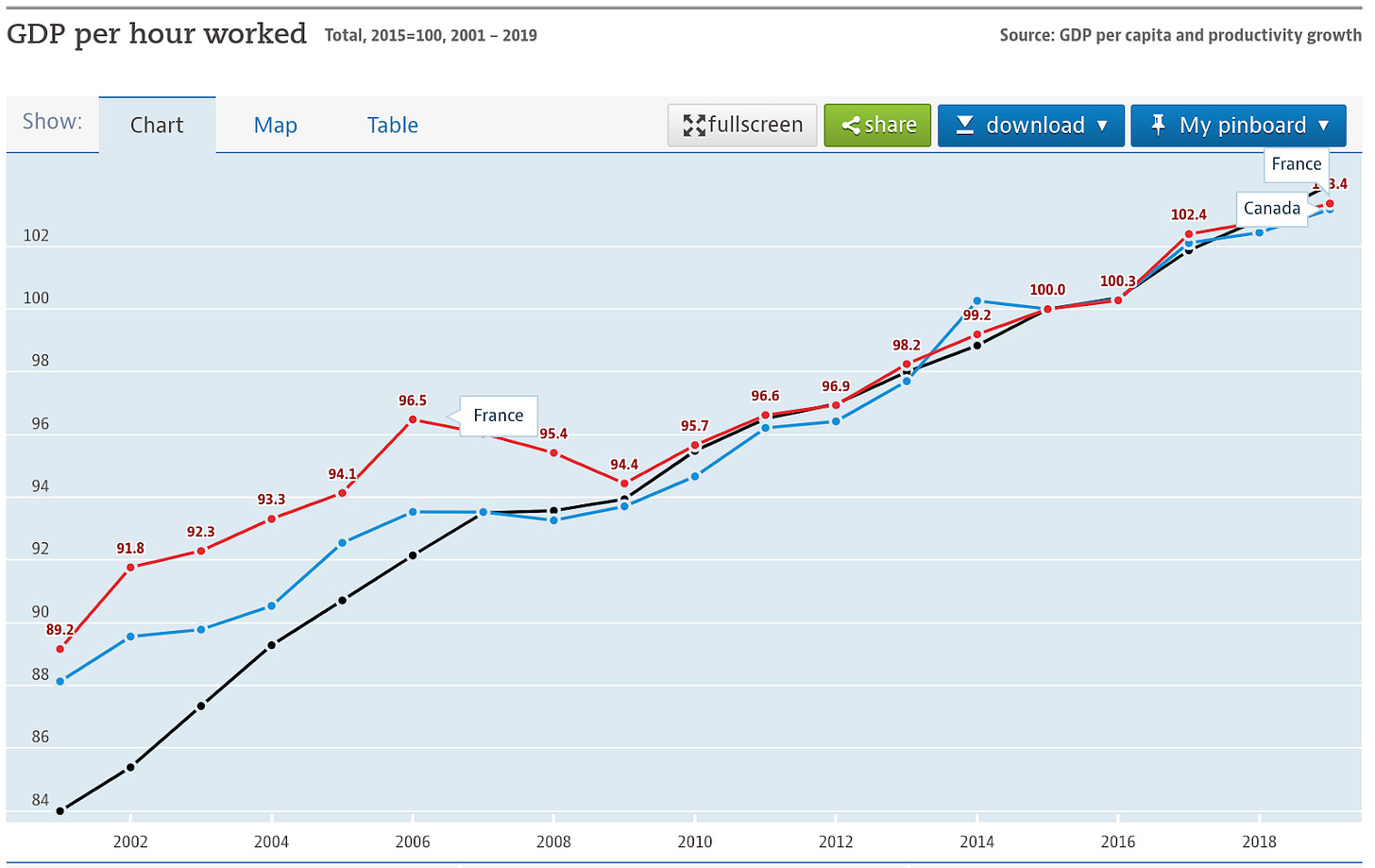

Say what you will about Parisian attitudes toward work—arrogant or annoying, whatever—but you can't argue laziness. When you take France and Canada's GDP per capita and divide them by their respective numbers of real hours worked you get the same number ($27.60). That's a big return on a much lower relative investment of time/life/vitality/expendable mental health. The human benefit is that they end up with more life to live. Over the course of a 30-year career, the average French person gets an extra 4,950 free hours to kill (30*165). Feels a bit unfair, almost.

Although their raw GDP per capita (41.5K USD) is a solid notch lower than ours (46.2K USD), I'd argue that the French standard of living is galactically higher than the numbers would imply. I found that most of my friends had a relaxed professional life without much hustle-culture stress, malaise, or uncertainty. For grad students and young lawyers, who are among the most stressed-out in North America, they sure get together for drinks and aperos way more than anyone I know back home. In Canada, you need a spreadsheet to schedule drinks with a friend. In France, it's a given when your group is going to meet, it's just a matter of at whose place.

Americanizing their work culture would be unthinkable. For North American yuppies, prioritizing work or schooling is the standard. For the French, to prioritize one's job is an aberration. Somehow, maybe a bit unintuitively, that makes them better at it.

/

This Ain't Ham

I stayed with a host family in Lorraine over Christmas and they asked me if I knew who Saint Nicolas was. Turns out it's not the guy with the red coat. Different dude entirely. Who knew?

The French legend of St. Nicolas, the patron saint of children, goes like this: Nicolas resurrects three children who were killed by an evil butcher who wanted to sell their meat as ham. A bishop buys the meat, thinking it's ham. Then comes Nicolas and, able to tell that they weren't actually ham but, in fact, human remains, goes “Hey, don't eat that” and takes the child meat from the bishop. Then he, appealing to God, puts the children back together. And that's, uh, why we have Christmas.

There are a few different renditions of the legend, but that's the gist. As far as I'm aware, the evil butcher story only shares a tangential-at-best relationship with Christmas. The day of Saint Nicolas’ feast falls on his designated day, December 6, which is smack in the middle of the Advent season. That's really about it. In Lorraine, the provincial region of France where I spent the holidays, the evil butcher story is still apparently a part of the Christmas folklore, passed down from grandparents to grandchildren. The same way Rudolph, or Santa, or whatever are a part of our own mythology.

The designated-saint thing isn't just for the holidays in France. On my birthday, in October, I was asked who my “saint” was and didn't realize until much later that, a) It's Saint Badouin, b) The French have designated saints for every day of the whole ass year, and c) There are, somehow, 366 entire saints in this world, if you count John Cassian, the lowliest, who got snubbed with the quadrennial February 29th.

The Catholic Church in France, to which somewhere between 41% and 88% of French people belong (if you include atheist/cultural Catholics), follows the liturgical calendar, which maps the cycle of the Christian seasons, feasts, and celebrations of saints. Lots of French people, Catholic or not, grow up observing feasts throughout the year, including on their “name day” (the day dedicated to the saint after which they're named). This partially explains why you get so many traditional names in France, or names derived from biblical origin, like Louise, Jean-Paul, Alexandre, François, etc. Every name has a day associated with it, every day with a saint.

There aren't any illuminations to be taken from this. Just a little tidbit for ya.

/

An Unexpected Positive Consequence of Density

I haven't seen a parking lot in four months.

/

Terrorism

When I first landed in Paris, I couldn't discern police from paramilitary from military. They blended together as one show of force. Originally I thought it was a covid thing. That they were deployed on every street corner and public square to maintain order, or enforce public health guidelines, or to make sure masks covered noses, or something.

I asked an employee, somewhere, why there were so many police/military/paramilitary/ambiguously-uniformed-people-with-guns standing around.

"Terrorism,” he said. As if I couldn't have possibly asked a stupider question.

Later I'd have friends and friends-of-friends ask me what surprised me most about France. My answer is that I wasn't expecting a police state. Not that the police presence isn't justified, but it was one of those things I never anticipated.

“Yeah, but there's terrorism,” they’d shoot back. As if I couldn't have been more ignorant to their situation. Eventually, I wouldn't be.

First was the stabbing of four men outside the Charlie Hebdo headquarters on September 25. The satirical magazine reprinted a controversial cover depicting the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Seven arrests were made in connection to the attack.

Second was the murder of Samuel Paty on October 16, a middle school teacher who was beheaded in broad daylight after depicting Charlie Hebdo's cartoons in a class on freedom of expression. Eleven people have been charged in connection to the attack, including some of Paty's students and their parents.

Third was the Nice stabbing on October 29 that killed three individuals outside a Catholic church, including the beheading of one of the victims. Three arrests were made.

Fourth was the shooting of a Greek orthodox priest on Halloween in Lyon, using a sawn-off shotgun. Critically wounded. One arrest. A few days prior, a group of men had surrounded the same priest while he was out for a jog and proceeded to torment and beat him before stealing his cross.

In turn, incidents of Islamophobia and xenophobia have popped up in France in the aftermath of the fall's spree of terror attacks. One notable incident is the stabbing of two Algerian Muslim women (and hijabis) under the Eiffel Tower on October 28.

It's a rough situation from every angle. On one hand, there's the French indigenous population contending with extreme variants of Islam not rendered as a theological construct but as a political ideology. French polling data indicates that the vast majority of Muslims in France (74%) acknowledge the conflict between their religious devotion and their desire to integrate into a secular, Western European culture. It doesn't help, of course, that the French fear of the unknown only serves to keep French Muslims on the margins and away from the social squares and structures that would facilitate their integration. Though it's worth noting that, despite what I heard about French people being abnormally xenophobic, opinion polling finds that “only” 22% of France has a negative view of Muslims, compared to 77% in Slovakia, 66% in Poland, 64% in the Czech Republic, and 58% Hungary. Even Sweden and Germany have a greater share of their population who view Islam in a negative light—so I'm not sure there’s anything particular about French chauvinism that might cause integration problems unique to their society.

I got to say, I was floored by the extent to which the French made a martyr of Paty, dying for the cause of free expression in an attack not against him alone but the whole of the republic. It's a value the French take seriously, and a commitment I share with the French. This is no surprise, as their republic was the first to constitutionally enshrine the right to free expression, under Article 11 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The U.S. revolutionaries, two years later, would use this as the basis of their First Amendment in 1791.

I think Macron did Paty a great honor by declaring him a hero of the republic and giving a live televised memorial service to his life and memory. Macron is an absolutely gifted orator, the best of the G7 leaders, and his speeches have not only helped me take my French language skills from a pitiful A2.1 to a slightly less pitiful B1.1, but have also supplied me with real insight into the austere respect and seriousness with which the French commit to fraternité. Tens of thousands showed up for memorial rallies across the country, marching for liberty, secularism, and democracy in a showing that spanned the political spectrum, comprising both right-reactionaries and left-radicals. Fraternity is not just a slogan in France. I don't think anything is.

If I can take anything from this, it's that I'm blessed to have grown up in a country mostly insulated from the threat of terrorism, and one whose immigration system works exceptionally well in vetting and integrating newcomers. Canada is a model for crafting immigration policy that welcomes migrants at a rate that allows civil society to keep pace, which we largely owe to three oceans sparing us from having to manage uncontrollable land borders. Our culture of accommodation is something more visible to me now that it's viewed against the relief of terrorism and separatism abroad. But it's a privilege more than it's a virtue, I realize.