Through one year in Ukraine, ordinary Canadians are exemplifying our country's civic internationlism

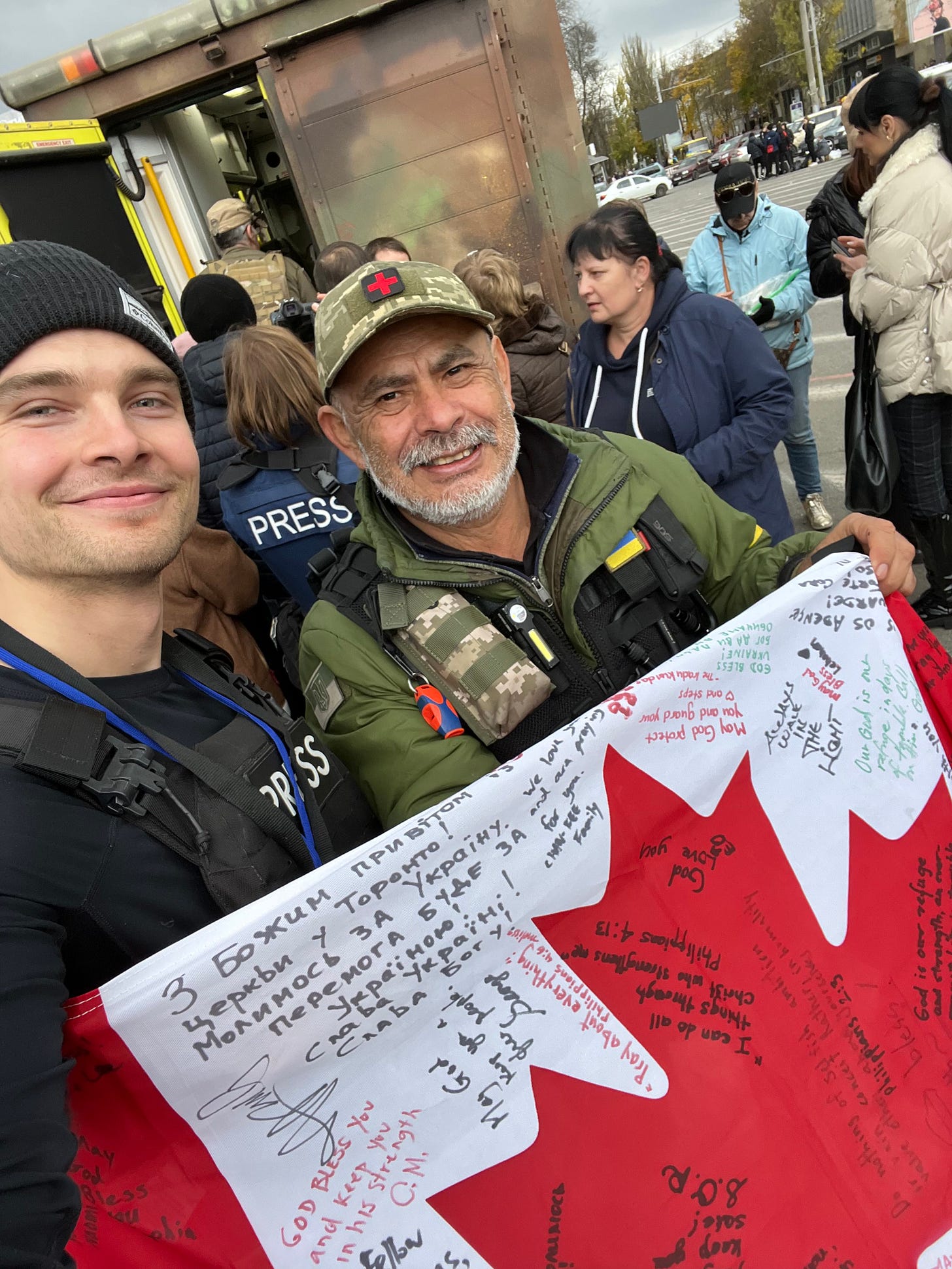

In the streets of Kherson, Nery Duarte waves a Canadian flag with signatures and well wishes scrawled in Cyrillic. A former missionary, the 62-year-old from North York has taught first aid workshops to Ukrainian civilians since the first weeks of the war.

“We, as Christians, have a firm mandate to support those who are hurting,” Nery told me. While true, the flag in his hands made me question to what extent our Canadian citizenship played a greater role in our being there than our Christian faith.

During international catastrophes, the Canadian identity is among the strongest signifiers of allyship. “As a Canadian serving in Ukraine, I’m always amazed at how well I’m received anywhere I go,” Nery said. “The Canadian flag is one of the ultimate symbols of solidarity in their struggle.”

Although Canada built its strong reputation in Ukraine through a long history of mutual support, volunteers like Nery have been working hard to sustain it over the past year.

So too has Kate MacEachern, 43, of Antigonish County, Nova Scotia. Kate helps run a small humanitarian organization, The Canada Way, alongside two other veterans from Atlantic Canada—Stephen Viscount and Jason McCormack, both 46.

The Canada Way operates a garage on the Polish border from which they run four vehicles into Ukraine multiple times weekly. Loaded with food and medical cargo, they deliver where few others dare to go, including active war zones in the Donbas.

“I came here to fight,” MacEachern said. “It wasn’t until I met up with Jason and Stephen […] that I realized I could serve a larger purpose as a humanitarian.”

Kate doesn’t see herself as a hero, but as someone coming to the aid of a friend. “None of us are saviours,” she told me. “We’re just a group of Canadians doing our best to see as many through to the end [of the war] as we can.”

In Kharkiv, I met father-son duo Paul and Mackenzie Hughes, respectively 58 and 20, who founded “H.U.G.S” (Helping Ukraine Grassroots Support), an NGO that operates near the Russian border. Since March, the two Albertans have made over 150 missions to liberated Ukrainian villages using a fleet of donated vehicles, dropping off critical food supplies and medicines that would otherwise be unobtainable for locals.

Every mission sees Paul and Mackenzie wager their lives so as to alleviate the suffering of others. In October, I discovered firsthand just how high the stakes were when they invited me on a run into recently liberated territory. While distributing aid parcels to villagers, two Russian fighter jets soared only a hundred meters or so directly overhead.

On the drive home, I asked Paul what motivates him to face such danger. “I hate bullies,” he said. “I’ve hated bullies all my life. My dad always taught me to stand up to them.”

As a food security activist and farmer, Paul decided to apply his passion for food accessibility to the Ukrainian war effort. “I thought I should stick to what I know, which is helping feed people,” he said. “All the food we grow in Calgary is donated to food access programs. I thought maybe this is what I should be doing here too.”

Whatever their motivations, the contributions of ordinary Canadians have played a critical role in the perception of our country in Ukraine. However tragic, humanitarian disasters such as these are generational opportunities to define the Canadian identity through acts both of the state and individual.

Since the inception of the United Nations (UN), Canada has forged its identity as a liberal peacemaker, using international institutions to mediate global conflict. Most notably in its involvement in resolving the Suez Crisis, for which Prime Minister Lester Pearson was awarded the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize. In all, 150,000 Canadians have served in UN peacekeeping missions to date, constituting 10 percent of the world’s deployed peacekeepers.

As Roland Paris notes, Canada has long balanced two competing images of itself: one of a liberal peacemaker, the other of a warrior nation characterized by “moral steadfastness and martial valour.” The Canadian humanitarians in Ukraine today, many of them veterans themselves, reflect both sides of Canada’s historical face.

While the federal government has rightly provided Kyiv with funding and firepower, in more limited supply is exactly this moral steadfastness required to fulfill the imperative to help. Those who’ve answered that call have earned more goodwill for Canada among individual Ukrainians than any act of the state.

At home, national pride can feel out of fashion due to historic wrongs and internal division. But in Ukraine, to be Canadian means something. Our actions have given our country an image of humble humanitarians—invaluable PR that even Ottawa cannot buy.

On the front, Canadian volunteers match conservative profiles: working-class veterans from the Prairies or the Maritimes, without flashy degrees or job titles. Some have troubled histories, others are just troubled; but they prove that anyone, with the right qualities, can be an ambassador for a big-hearted, dignified Canada that we can all be proud of.

Paul Hughes, for his part, wants nothing in return.

“I just have my farm, I don’t need anything,” Paul said. “I live very simply.”